French Impressionist Films (1918 - 1929)

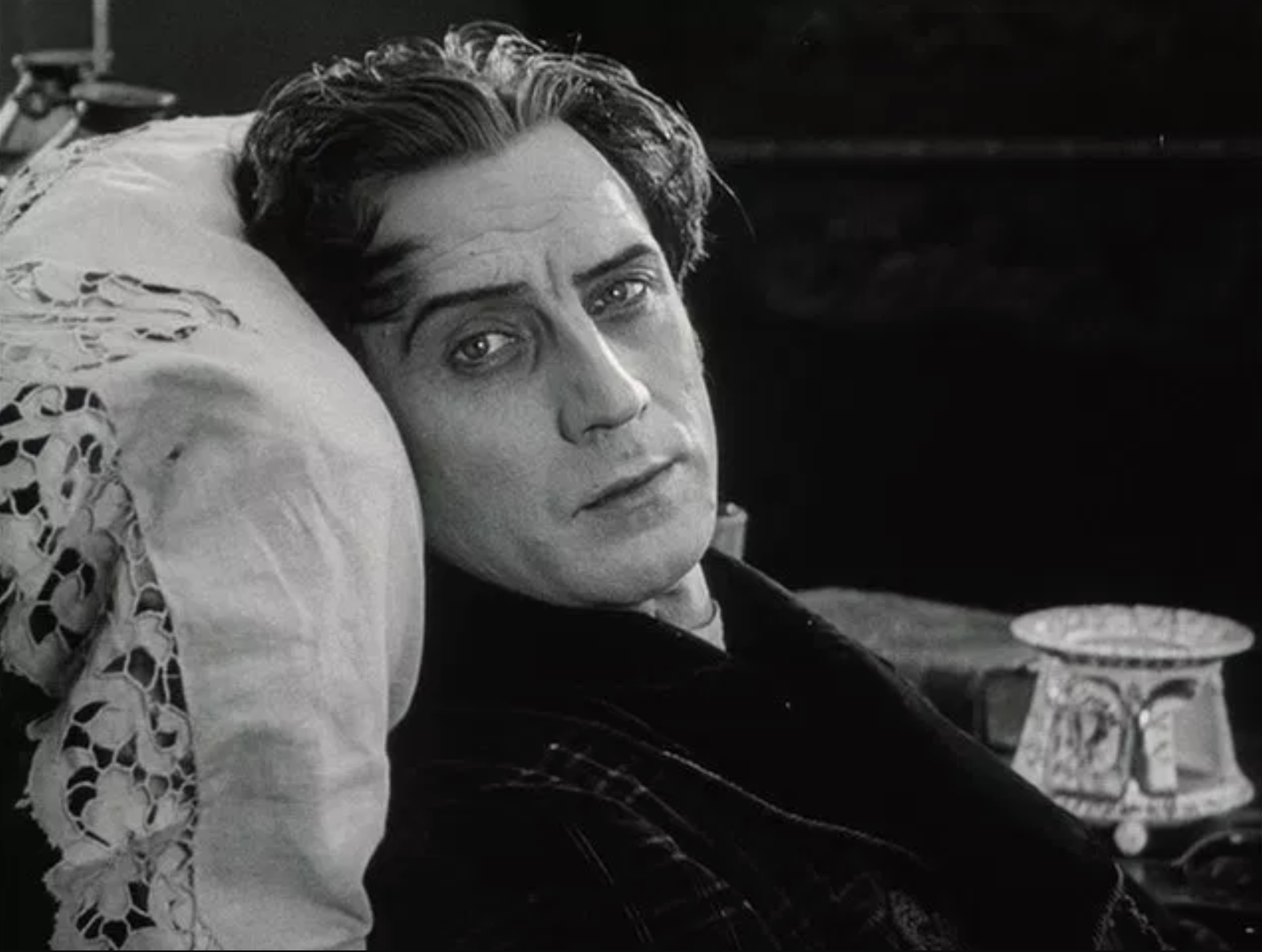

/J'Accuse (Credit: United Artists, pathé)

In post-War France, a generation of filmmakers had become eager to explore the limits of film as an art form. This was aided in-part by the belief that America was crafting more lively, interesting productions by 1918, and the French industry was at risk of losing its own audience. A crisis within the French industry developed, allowing filmmakers the opportunity to produce ambitious films focused on beautiful aesthetics and psychological exploration.

Impressionist cinema had varied success at the box office, and many key figures within the movement would juggle these productions with more commercial fare. Germaine Deluc would make sociopolitical films alongside popular dramas, while Jean Epstein continued his successful career as a costume designer alongside his directorial efforts. Despite this, the Impressionists managed to keep the movement alive for over a decade, reclaiming France's national identity in relation to cinema and the avant-garde.

The Tenth Symphony (1918) La Dixième Symphonie – by director Abel Gance

An orphan falls under the spell of an evil man and becomes his mistress. She is eventually able to find a new life with a famous composer, but her past may soon catch up with her and potentially destroy her new love. The film was financed by Charles Pathé; By 1919, Gance would create his own production company, Films Abel Gance, but Pathé would continue to finance and distribute the director's productions.

Rose-France (1919) – by director Marcel L'Herbier

Known for its patriotism and heartfelt sentiments, Rose-France comments on the end of WWI and is known for L'Herbier's experimental techniques. It would be the director's first film, firmly establishing him as an exciting, innovative filmmaker.

J’Accuse! (1919) J'accuse – by director Abel Gance

J'Accuse (Credit: United Artists, pathé)

After enlisting to fight against Germany in WWI, a man suspects his wife committing adultery with a local poet. He sends his wife to live in Lorraine and ends up fighting alongside the guilty poet in the same battalion. The man eventually returns home to discover that his wife, who was raped by German soldiers, now has an illegitimate child.

J'Accuse! addresses the devastation of WWI, and is often considered to be a pacifist film. It was a huge success both in France and overseas, and quickly established Abel Gance as an industry leading director.

Man of the Sea (1920) L'homme du large – by director Marcel L'Herbier

Man of the Sea (1920) by Macel L'Herbier (Credit: Gaumont)

Based on a short story by Honoré de Balzac, Man of the Sea centers on Nolff, a fisherman who has just fathered a son. He desperately wants his son to follow in his footsteps, but as the son grows older he becomes a disappointment.

Macel L'Herbier previously had success with Le Carnaval des vérités, and used Man of the Sea to discuss how human behaviour is formed through the forces of good and evil. The coastline plays a key role in the film's overall tone, a technique the director also used in Le Torrent. The director claimed that this is the first film in which the audience experiences a flashback, and Man of the Sea is also celebrated for L'Herbier's innovate use of intertitles; choosing to integrate them into the frame as opposed to traditional cutaways.

Fiève (1921) – by director Louis Delluc

While on vacation, a married woman encounters an old flame. Prior to Fiève, Louis Delluc had published Le Journal du Ciné-Club and consequently founded Cinéa in 1920.

Eldorado (1921) – by director Marcel L'Herbier

Eldorado (Credit: Gaumont)

Sibilla is a gypsy dancer living in Seville. When the financial strain of her son's medical bills become too great, she seeks help from his biological father. Despite being incredibly wealthy, the man refuses to help - but Sibilla will stop at nothing to ensure the safety of her son.

Eldorado was celebrated upon release for its innovative techniques, which were seen as quintessentially French at the time. The film is an amalgamation of L'Herbier's ideas previously utilized throughout his filmography, adapting them for a broader appeal. It was important to L'Herbier that a distinction was made between his techniques in optical distortion and those seen in German Expressionist film, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. While the former uses camera trickery to communicate ideas such as a character's lack of focus, the latter uses sets and props to portray a subjective reality.

The Woman From Nowhere (1922) La femme de nulle part – by director Louis Delluc

An ageing woman returns to a villa she has been avoiding for years. Upon arrival, she encounters a younger woman now facing the same as her, 30 years later.

Just like Germaine Dulac, Louis Delluc had previously been a successful writer. In 1917, he wrote for Cinéa and Le Journal du Ciné-club before taking up the director's seat in 1920.

The Smiling Madame Beudet (1923) La souriante Madame Beude – by director Germaine Dulac

A woman grows tired of her loveless marriage. She contemplates the murder of her husband, who regularly jokes about his own suicide.

Prior to filmmaking, Dulac had been writing for feminist magazine La Fronde from 1900 until 1913. She ultimately decided to create D.H. Films with Irène Hillel-Erlanger. The venture lasted from 1915 until 1920, and undoubtedly led to The Smiling Madame Beudet, one of the industry's first ever feminist films.

The Wheel (1923) La roue – by director Abel Gance

The Wheel (Credit: Pathé)

A railwayman and his son fall in love with Norma, a beautiful young woman who had been saved from a near-fatal train crash and welcomed into their family as a child. The Wheel is celebrated for its innovative lighting techniques and rapid editing. The original cut was reportedly nine hours long, and foreshadows many techniques that would later be seen in Napoléon, the title for which Gance is best known.

Praising The Wheel with the highest esteem, legendary French filmmaker Jean Cocteau once said "there is cinema before and after La roue, as there is painting before and after Picasso".

The Faithful Heart (1923) Coeur fidèle – by director Jean Epstein

With a dead-end job and a partner with a severe drinking problem, Marie dreams of running away with Jean, a local dockworker. The Faithful Heart tells the story of her struggles and how she is driven to extreme circumstances. Jean Epstein was already an established film theorist by the time the film was released, having written several books on the medium. He wrote the film is one night and hoped the melodrama would appeal to a wide audience. The director was notably influenced by The Wheel, and Coeur fidèle shows Epstein's own developments on Abel Gance's techniques, including but not limited to lens distortion, rhythmic editing and montage. Despite this, The Faithful Heart can be considered to be realist, and was 'stripped down' in comparison to typical melodramas at that time.

Don Juan et Faust (1923) – by director Marcel L'Herbier

Based on the German stage play by Christian Dietrich Grabbe, director Marvel L'Herbier envisions a meeting between a fictional libertine and a German legend. A disagreement between L'Herbier and Guamont about the film led the director to create his own production company, Cinégraphic.

Crainquebille (1923) – by director Jacques Feyder

Also known as Bill, Old Bill of Paris and Coster Bill of Paris, the film centers on a grocery seller in a Parisian market. After 40 years of working in the market, a policeman suddenly asks the seller to move along, causing a significant turning point in the old man's life. In particular, Crainquebille was praised for its striking realism.

The Seller of Pleasure (1923) Le Marchand de plaisir – by director Jaque Catelain

Le Marchand de plaisir marked Jaque Catelain's directorial debut, in which he would also play the lead role. Prior to this, Catelain was (and still is) best known as a prominent actor throughout L'Herbier's filmography.

The Little Kid (1923) Gossette – by director Germaine Dulac

An orphan is adopted by a couple with a fugitive son. Gossette is based on Charles Vayre's novel of the same name.

The Burning Brazier (1923) Le Brasier ardent – by directors Ivan Mosjoukine & Alexandre Volkoff

Elle and her wealthy husband are constantly on bad terms. Although she enjoys being catered for, Elle questions her husbands love, while he becomes consumed by the threat of his rivals.

The Inhuman Woman (1924) L'inhumaine – by director Marcel L'Herbier

L'inhumaine (Credit: Cinégraphic)

Every man wants to be loved by Claire Lescot. A young scientist is left wanting to commit suicide after being mocked by the famous prima donna.

Hugely controversial upon release, The Inhuman Woman was created as a celebratory collaboration of the decorative arts. L'Herbier's primary interest with the production, besides the attempt to regain control of his finances, was to create stimulating visuals and embrace the skills of his collaborators. As L'Herbier claimed, The Inhuman Woman is a "miscellany of modern art," and his collaborators included French operatic soprano Georgette Leblanc and novelist Pierre Mac Orlan.

The Lion of the Moguls (1924) Le lion des Mogols – by director Jean Epstein

Grand Khan has been usurping power over Tibet for 15 years. He captures the love of Prince Roundhito-Sing and forces him into exile. The Prince ends up in Paris, where he is hired as an actor. But how long can he ignore his unresolved troubles back home?

The Lion of the Moguls is Epstein's first production for Films Albatros, which had been set up by Russian exiles in 1917 after the Russian revolution. He was given access to the Russian Cinema School of Paris and was asked to create a film that would be more commercial than his previous efforts. Epstein met these expectations half-way, shooting the Tibetan scenes in a traditional manner while utilizing his preferred techniques for Parisian sequences.

The Beauty from Nivernais (1924) La Belle Nivernaise – by director Jean Epstein

Bargeman Louveau adopts an abandoned boy, Victor. Years later, the boy falls in love with Louveau's daughter. Bargeman then discovers his adopted son's true heritage, a potentially disruptive revelation for Victor's future.

The Freak Show (1924) La Galèrie des monstres – by director Jacque Catelain

After a man kidnaps a young girl, they join the circus and travel to Spain. La Galèrie des monstres would be Jacque Catelain's second and final film as a director. The actor-turned-director would also play the leading role, while Marcel L'Herbier would be credited for his art direction.

Edmund Kean: Prince Among Lovers (1924) Kean – by director Alexandre Volkoff

Edmund Kean: Prince Among Lovers (1924) by Alexandre Volkoff (Credit: Films Albatros)

When a shakespearian actor falls in love, his professional and personal affairs between to entwine.

Catherine (1924) – by director Albert Dieudonné

With a script from Jean Renoir, director Dieudonné appears in the film. Dieudonné was a prominent actor throughout Abel Gance's early filmography, having played parts in five pictures between 1915-1916. In 1927, he would play the titular role in Gance's Napoléon.

The Irony of Destiny (1924) L'Ironie du destin – by director Dimitri Kirsanoff

Without realizing that he is in the wrong city, a man confuses his home with the home of a stranger.

Director Dimitri Kirsanoff is known for being the Impressionist with by far the least means available to him. Despite this, the director contributed a number of Impressionist films that held their own throughout the decade.

The Flood (1924) L'lnondation – by director Louis Delluc

The Flood (1924) L'lnondation by director Louis Delluc (Credit: Cinégraphic)

Based on Andrée Cortis's short story, L'Inondation takes place in a small village on the Rhone river. When a farmer refuses the advances of a young woman, the river's water level begins to rise, flooding the village.

While shooting the film, Louis Delluc contracted pneumonia due to the production's poor weather conditions. He passed away a week before the film was released.

L'affiche (1925) by director Jean Epstein

A flower girl is impregnated by a wealthy man, who leaves her to raise the child alone. The mother then enters her child's portrait into a photography competition, with disastrous results.

The Devil in the City (1925) Le diable dans la ville – by director Germaine Dulac

In the 15th century, smugglers in a small town settle in an abandoned tower. However, a mysterious figure purchases the tower, and rumors begin to circulate that the man was sent by the devil himself.

Children's Faces (1925) Visages d'enfants – by director Jacques Feyder

A young boy struggles to accept his mother's second marriage after the untimely death of his father. The young boy is played by Jean Forest, who Feyder had discovered on the streets of Montmarte and had previously cast in Crainquebille.

The Living Dead Man (1925) Feu Mathias Pascal – by director Marcel L'Herbier

The Living Dead Man (1925) by director Marcel L'Herbier (Credit: Films aRMOR)

Based on Luigi Pirandello's Il fu Mattia Pascal, L'Herbier's adaptation centers on Mathias, who married Romalinda despite her wretched mother. Unfortunately, his mother-in-law turns his home life upside down. After a family tragedy, Mathias leaves his hometown and finds fortune in a Casino, only to return home and discover that he has been declared dead by the local paper. Free from his old life, he has an unusual opportunity to have a fresh start.

The Living Dead Man marks the early beginnings of Lazare Meerson, who would go on to become widely acclaimed for his art direction in the French film industry throughout the 1930s. Unfortunately for L'Herbier, the film was originally shown in two parts, despite the director feeling that this had a negative impact on the audience's reception.

The Daughter of the Water (1925) La Fille de l'eau – by director Jean Renoir

La Fille de l'eau ( credit: les films jean renoir)

La Fille de l'eau ( credit: les films jean renoir)

Also known as The Whirlpool of Fate, Renoir's 1925 title takes place in the 19th Century. After the death of her father, a young woman is stricken with poverty. She ultimately leads a life of crime with disastrous consequences.

Mauprat (1926) – by director Jean Epstein

Mauprat (credit: Les Films Jean Epstein

Based on George Sand's novel of the same name, the film centers on Bernard De Mauprat. As an orphan raised by untrustworthy aristocrats before the French Revolution began, he is saved from the gallows by his father, a noble knight. Bernard's return then causes despair among his family as he attempts to seduce a knight's fiancée.

Luis Buñuel was working for Jean Epstein as an production assistant at the time, and even has a small role in the film. In the same year, Epstein founded Les Films Jean Epstein.

Gribiche (1926) – by director Jacques Feyder

Gribiche (1926) by director Jacques Feyder (Credit: fiLMS alBATROS)

A working-class teenager is adopted by an American millionairess. He is promised a valuable education, but his life is also about to get far more complicated. The film is based on Frédéric Boutet's 1925 novel of the same name.

Menilmontant (1926) – by director Dimitri Kirsanoff

Menilmontant (1926) by director Dimitri Kirsanoff

Menilmontant (1926) by director Dimitri Kirsanoff

By the time Kirsanoff released Menilontant in 1926, he was already a leading figure of the Parisian avant garde. Named after the Parisian neighborhood in which the film is set, Menilmontant explores the details of a murder. The film is remembered for its extreme close-ups, double exposures, handheld camerawork and the application of soviet montage theory.

Nana (1926) by director Jean Renoir

Nana (1926) by director Jean Renoir (Credit: lES Films Jean Renoir)

When a beautiful young actress fails to please the Théâtre des Variétés' audience, she decides to use her sexual prowess and enigmatic charm on wealthy men instead. But will Nana's exploits bring her everything she desires, or ruin the lives of everyone involved?

Nana is based on Émile Zola's novel of the same name. The production is Jean Renoir's second feature film and stars his wife, Catherine Hessling, as the titular character. The film failed to make a profit, making it impossible for Renoir to finance a production with Nana's extravagance for years. Despite this, the film is remembered for a number of stunning set pieces and is a valuable addition to the legendary filmmaker's oeuvre.

Six et demi onze (1927) by director Jean Epstein

Six et demi onze (1927) by director Jean Epstein (Credit: Films Jean Epstein)

A man abandons his brother, with whom he lives and works, in order to be with his new-found love, Maria. She eventually returns to the stage, leading to the man's suicide. In a cruel twist of fate, the man's brother, a renowned doctor, then falls for Marie, having no knowledge of her relationship to his brother, or the real reason he took his own life.

Six et demi onze was written by Marie Epstein, Jean's sister and frequent collaborator with director Jean Benoît-Lévy. Epstein and Lévy worked on 16 films together, creating a collective filmography that was consistently focused on morality and contemporary societal issues. She is also known for her restoration work post-1950, including the preservation of Abel Gance's Napoléon.

Napoléon (1927) Napoléon vu par Abel Gance

Napoléon (Credit: Gaumont)

An epic in every way, Abel Gance's Napoléon centers on the famous French general, particularly focusing on his youth and the early days of his successful career within the military. The film is overwhelmingly ambitious for its time thanks to plethora of innovative techniques. For example, consider Napoléon's fluid camera movement. While German Expressionist filmmakers were being praised for 'entfesselte Kamera techniques' (guerilla filmmaking such as strapping a camera to a cinematographer riding a bicycle) in the same year, Napoléon takes even more complex camera movements and applies them to an production of epic scale. The film is also celebrated for advancements in film theory, such as point-of-view shots, innovative superimposition and multi-screen projection.

Perhaps the most striking technique used in the film is Abel Gance's decision to present Napoléon's finale in a 4.00:1 aspect ratio, projecting three 1.33:1 reels side by side. The film was so groundbreaking and important to the medium's history that it even influenced the French New Wave more than 30 years later.

The Three-Sided Mirror (1927) La glace à trois faces – by director Jean Epstein

The Three-Sided Mirror (1927) by director Jean Epstein (Credit: films jean epstein)

Three women collectively look back on their love affairs with the same man. The opinions of an upper class English woman, a Russian artist and a working class woman pain a portrait of a cowardly man.

The Three-Sided Mirror is based on Paul Morand's short story of the same name. Epstein was priased for the film, specifically due to the avant garde manner in which he adapted Morand's writing. The techniques used throught the film are said to be a source of inspiration for The Left Bank's Alain Resnais and his 1961 film, Last Year at Marienbad (L'Année dernière à Marienbad).

Marquitta (1927) – by director Jean Renoir

A street singer called Marquitta becomes Prince Vlasco's mistress, but when his jewellery goes missing she's the first to be blamed. Years later, Vlasco ends up begging on the street, and is helped by his former lover. Their tumultuous relationship continues and the truth behind the missing jewellery is finally revealed.

Little Devil May Care (1928) Le diable au coeur – by director Marcel L'Herbier

A fisherman's daughter falls in love with a boy who comes to live with her family. Little Devil May Care is a story of remorse, sorrow rekindled love, based on Lucie Delarue-Mardrus's novel of the same name. Unlike many other films from the era, Le diable au coeur can be found entirely intact in film archives.

Autumn Mists (1928) Brumes d'automne – by director Dimitri Kirsanoff

Kirsanoff's film uncovers the mysteries of a woman burning letters on the stove.

The Fall of the House of Usher (1928) La Chute de la maison Usher – by director Jean Epstein

The Fall of the House of Usher (1928) by jean epstein (credit: film jean epstein)

Based on Edgar Allen Poe's short story of the same name, acclaimed critic Roger Ebert once described the hallway seen in the film as one of cinema's most haunting spaces. He also noted that it is a possible inspiration for Citizen Kane.

The Little Match Girl (1928) La Petite merchande d'allumettes – by director Jean Renoir

With fantasies of purchasing something from the toy store, a poor frozen girl tries to sell matches during Christmas time. The film is based on Hans Christian Andersen's short story, and stars Renoir's first wife, Catherine Hessling.

Money (1929) L'Argent – by director Marcel L'Herbier

Based on Émile Zola's novel of the same name, L'Argent tells the story of Paris's stock market throughout the 1920s.

L'Argent was a huge production that was partly financed by UFA, the company which had also created many German Expressionist films throughout the decade. This is why Alfred Abel, the actor who would become best known for playing Joh Fredersen in Fritz Lang's Metropolis, appears in the French production. Ultimately, L'Argent would tarnish L'Herbier's relationship with his co-producer, Jean Sapène, and would be Cinégraphic's final film.

Financial Woes and Impressionist Directors in Sound-era Cinema

In 1928, L'Herbier's cinégraphics was absorbed by Cinéromans, and Les Films Jean Epstein would also go out of business. The enduring need to create commercially successful films prevailed, as this quick succession of financial failures ultimately marked the end of the Impressionist movement.

Gance directed La Fin du monde in 1931, his first talkie, while Epstein is credited for creating the first ever Breton-speaking film, Chanson d'Armor. Living up to his reputation as an innovator, L'Herbier made the first fully talking film by a French production with 1929's L'Enfant de l'amour, leading to a brief hiatus where he focused on his writing. By far the most successful Expressionist in sound-era cinema, however, was Jean Renoir, who is now perhaps the most acclaimed French director of all time.

Renoir would go on to make revered, hugely influential titles such as La Règle du Jeu and La Grande Illusion in the late '30s before immigrating to Hollywood to escape the German invasion of France in 1940. Needless to say, the collective determination of these groundbreaking directors led to a number of milestones, and their communicative visual styles and messages on social morality have been an enduring influence on aspiring filmmakers.

References

Kevin Brownlow. Essay in booklet accompanying DVD edition of J'accuse by Flicker Alley, 2008. p. 11.

Booklet accompanying the CNC/Gaumont restoration of L'Homme du large issued on DVD in 2009; pp.8-9.

Richard Abel, French cinema: the first wave 1915-1929. (Princeton U.P, 1984) p.308-312.

Colin Marshall (18 November 2015). "The First Feminist Film, Germaine Dulac's The Smiling Madame Beudet (1922)". OpenCulture. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

Dave Kehr (May 6, 2008). "New DVDs: 'La Roue'". The New York Times.

Jean Epstein. Présentation de "Cœur fidèle", in Écrits sur le cinéma, 1, 124 (jan. 1924) [quoted in Richard Abel, French cinema: the first wave 1915-1929 (Princeton University Press, 1984), p.360.

Marcel L'Herbier, La Tête qui tourne. (Paris: Belfond, 1979). p. 102.

Jaque Catelain, Jaque Catelain présente Marcel L'Herbier. (Paris: Vautrain, 1950.) pp. 91–92.

Brownlow 1968, p. 518

Mast, Gerald; Kawin, Bruce F. (2006). A Short History of the Movies. Pearson/Longman. p. 248. ISBN 0-321-26232-8.

RogerEbert.com (Review: The Fall of the House of Usher)